How one special woman – a daughter, sister, mother, grandmother and dear old aunty – ran her own race in a very different Victoria.

*

I have a small block of land in country Victoria, where I’ve recently planted around 400 trees, bushes, grasses and flowers. They’re all natives, meaning right now they are a rough and attractive mix of coarse, serrated leaves and robust, prickly blossoms.

But there is one garden patch devoted to something else – something altogether more delicate – the pretty little perennials of my dear Aunty June.

In my driveway circle, there’s a plot of June’s white and yellow jonquils, with their paper-thin petals. A line of her pendulous bluebells sprouts every year along my front verandah. Once in a while I see the gigantic pink trumpets of my aunt’s belladonna lilies. And in between are the spotted fronds and orange tubes of her lachenalias, rising up to say hello as the air turns warm.

The latter were the last bulbs she gave me before she passed away. June Beverley Alston was 91 when she died in May. She had a hard life, too, but I think she found something magical – evanescent even – in all those petals and stems. It shines through when reading over the loose transcript of her biography, which she told to a digital recorder over several days in her 80s, when she could barely see anymore.

She was born on a farm in Nar Nar Goon in 1926. The local nurse, Fatty Osborne, stopped by to help. Then life resumed as normal on the green Gippsland dairy farm, although “normal” meant something altogether different then.

In that place and time, a childish delight could be as simple as visiting the neighbour, Mrs Pavlich, who had an array of fine cups and saucers and – thrillingly – let little June sip her milky tea from a China cup. A darker memory was the death of her baby sister, Irene, of Pink’s disease. June visited Irene in hospital, climbed up into the cot to see her, and the nurse slapped her leg. June always remembered that slap, and how her little sister’s coffin was put into a car and driven away to Bunyip Cemetery.

“Otherwise,” June said, “life just trundled along.”

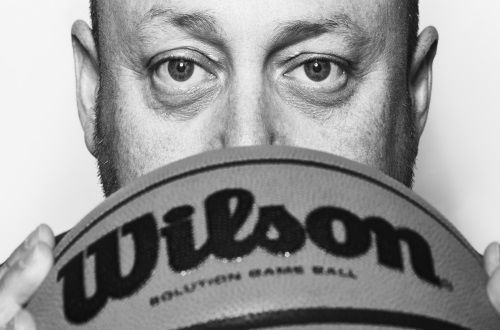

June Alston with her great-nephew Charlie, Konrad Marshall’s son.

The family had 77 acres for 50-odd jersey cows. Each once had a name. June was fond of Camilla and Merina. Every day brimming cans of milk were shipped to Melbourne for processing at the Nirvana Dairy in Spotswood, except for a few spare billies-full, which they sold in town. It was the kind of life in which you make your own soap, rooms are lit by kerosene, the house is kept warm by the slow combustion stove in the kitchen, and freedom – for a little girl on a farm at least – meant summer days wading into a clear pond to pick water lilies.

June remembered the day a local boy accidentally loosed a shotgun, and a few pellets flew through the shed wall and into the scalp of her sister, my aunty Tup. While Tup recovered she was given the most beautiful double-jointed doll with white porcelain teeth. June could scarcely have been more jealous.

During drought or flood or famine, men would come by the property looking for odd jobs and a few bob, and so a cast of travelling hawkers and colourful locals drifted in and out of her life. Mr Guyscar had a covered wagon, like a gypsy, and he would stay overnight and let his horse roam while he sold ribbons and lace, buttons and press studs. Diamond Gig would come by selling apples. Smoland the greengrocer flogged wooden crates of veggies. The water diviner, Michelly, would visit with a forked stick in his hands and point – there! – to the spot where a borer might be sunk.

June remembered sitting high on the backs of the Clydesdales – Prince and Jess and Duke – and walking up and down the fields in rows, spreading super on the paddocks and planting peas and tomatoes. She remembered dragging scrap wood and fallen ironbark branches into town for the bonfires of Guy Fawkes Night.

June Moore – as she was then – with her bicycle in 1943.

She fed sickly sweet toffee to her little brother, my uncle Ken, and then went mushrooming with him in the sun between the gumtree glades, before walking down to the Princes Highway with their haul in paper bags. As the cars rushed by to other places, the children held up their quarry and roared: “Mushies for sale!”

With her big brother, my uncle Norm, she shared a natural ability as a runner. But word arrived one day that a faster girl from the school in Cora Lynn was coming to beat June. “And I thought ‘by crikey she won’t!’. And we took off and I thought ‘she’s not going to beat me’. Anyway, I beat her.”

The school burned down once, and so they had classes in the Mechanics’ Hall, and the kids of the town roamed the streets playing chasey and hopscotch. She went to a barn dance dressed in pink with fancy frills, desperate to try the three-hop polka.

Still, every morning she fed the cows a saucepan of bran and chaff. She nudged the laggards towards to the hay bales. She helped operate the milkers with their dangerously exposed motors and big leather pulleys. Her mum, my grandmother, was a staunch worker and stoic woman. “She was a real Briton, but I don’t think she ever got any sort of thanks for it.”

June digs an air-raid shelter in Hampton Park in 1942.

June well remembered the day her dad, my pop, brought home an Austin Tourer – one of only two cars in the district – to replace their old horse and jinker, and how it made the Moores feel like gentry. Yet they moved like vagabonds. Pop dragged them around chasing one idea or the next: dairy farming, veggie growing, stone fruit orchards, a cake shop and coal trucking.

Men were often like that in those days. “There’s money to be made in that,” they’d say. “Let’s give it a try.” And so they lobbed into a tumbledown shack in Hampton Park, then a rented house in Cranbourne. A bakery in Aberfeldie. A shared house in Murrumbeena.

June’s first escape was riding her bike to Lyndhurst station and catching the train to Bradshaw’s Business College to learn dressmaking. She got a job with a tailor, and sat all day sewing hooks and eyes on skirts. Later she worked at The Lattice, an upper-class tearoom in the Block Arcade – a weekly pay rise from 11 shillings and 9 pence to two whole pounds.

The war had started, and the young soldiers would march around Melbourne, and so the girls were allowed go out into the city streets in turns to cheer them on. June had a boyfriend, Kevin Crowley, and the pair caused a family scandal by staying out all night together. Kevin enlisted soon after, and was killed in battle not long after that.

June marries Jack Alston in March 1948, with her sister Dorothy as flower girl.

June, then 17, remembered eating a sandwich of potted meat on the day my mother, Dorothy, was born. Immediately she learned to knit and crochet, and made my baby mum little matinee jackets and collared dresses.

Still moving from house to home to shack at the whim of an itinerant pop, they landed at Koo Wee Rup, where he planted carrots, then the foreshore at Tooradin to grow asparagus. One night, in complete darkness, they arrived at dusty new digs in Romsey, and began setting up house by plugging holes in the water tank with chewing gum.

In one destination, the Alstons lived next door. There were four brothers in the family, and one day one of the boys got out of his truck.

“I’m Jack,” he said. “I’m June,” she replied.

Jack and June’s first date was an afternoon at Hanging Rock, and soon they were married and living in a log cabin in Cherokee. June fetched their water from deep within the bush – a fresh spring that was like ice, even in summer. Jack killed the tiger snakes – picking them up by the tail, whizzing them around his head, then snapping their backs like he was cracking a whip.

June had three children – my cousins Lindy, Elizabeth and John – but Jack barely got to know them. In April 1953, a tractor rolled on top of him. He was 26 when he died.

June’s lachenalias in full bloom.

June raised her children alone in Winchelsea on the Barwon River. For a long time she cleaned the local primary school. I remember staying with her in my holidays, spending idle hours sprinting alone through the empty school while she ran the electric buffer up and down the linoleum corridors. She built a life there, competing in flower shows and cake shows, making the lightest sponges with the heaviest whipped cream, and pink jelly cakes with coconut flakes.

She was like a grandmother to me. I spent almost every school holiday there. We watched the tennis together. She loved the polite and determined Ivan Lendl and naturally had no time for John McEnroe. She made me toast with butter every morning and tucked me in at night. If I begged hard enough, she would gruffly clear the huntsmen out of the high corners of the bedroom ceiling.

Aunty June’s presence lives on in the flowers she grew.

I used to give June an orchid every year on her birthday, which she kept in an overgrown greenhouse colonised by harlequin bugs. It was part of her almighty ramshackle garden. Nothing is left of it now. Her house was torn down when she moved into the retirement home two doors down. The land was turned over by bulldozers.

But her flowers live on in several gardens. All those jonquils and daffodils, bluebells, lilies and lachenalias – they’re blooming right now, and that seems right.

June’s birthday was this week, you see – September 21 – right in the perfumed heart of spring. It’s that time of year when the wind warms the topsoil, the sunshine nurtures the seed, and the scent of the flowers is sweeter not just for those who have grown them, but those who know the place from which they come.