A third of Indigenous AFL players, and some of the game’s spectacular legends, come from one language group. What gives them their edge?

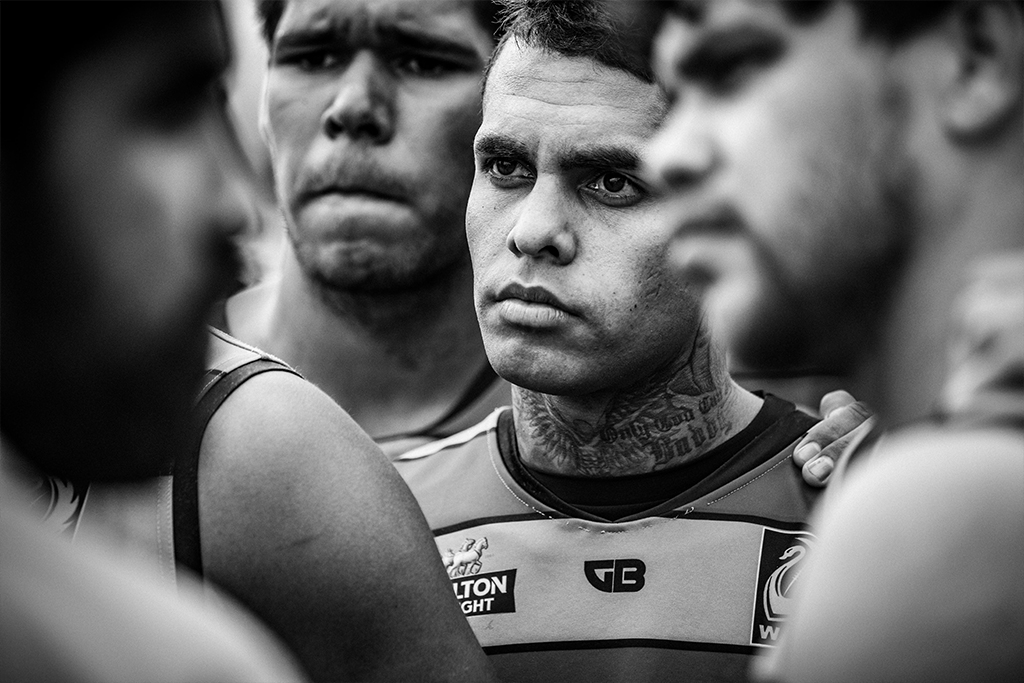

The last slice of sunset over the Indian Ocean is burnt orange, and the sky above is limitless black. Two globes on steel poles throw faint illumination over this suburban Perth footy ground, but the real light comes from the full moon sliding behind grey clouds. The boys from the Nollamara Amateur Football Club are training on the spongy grass.

“Mine! Mine!” cries a forward.

“Gotta go! Gotta go!” says the defender.

“That’s the way,” roars their skipper. “That’s the way!”

Tonight is a scratch match between bibs and guernseys, seniors and reserves. As team selection nears, the pretty play gives way to something harder. Knees driven into kidneys. Elbows to the neck. Gang tackles. Sling tackles. Spear tackles.

The “Nollaroos” aren’t the best, occupying the lower reaches of the local amateur competition, but they are undefeated after five games within Division C3. And, with a yellow Sherrin pinging from one end of the dewy oval to the other, they fly through the night dreaming of great moments and famous players – their uncles and nephews, brothers and cousins.

This team is close to 100 per cent Indigenous, and its players belong to a specific Aboriginal society. They are members of the Noongar nation, the most dominant cultural force in the history of Australian rules football. Most Aboriginal tribes, clans or language groups have only a few members playing in the highest league in the land. Hawthorn champion Shaun Burgoyne, for instance, is the sole man with Warray heritage playing in the AFL. Two Wangkathaa men play in the league right now: Eddie Betts and Daniel Wells. There are four Tiwi. Four Larrakia. Four Palawa. The Narangga in South Australia boast an admirable five players, and the Yorta Yorta from Victoria have six.

But the Noongars are different. They have 25. Enough for an entire team. And a star-studded team at that. Three Hills. Two Yarrans. Two Garletts. Two Jettas. Two Bennells. Two Ah-Chees. How about Paddy Ryder, Michael Walters and Michael Johnson? How about the one and only Lance “Buddy” Franklin?

Of the 73 Indigenous players in the AFL right now, one in three are Noongars.

This is not a recent influx, either. Polly Farmer? Noongar. Barry Cable? Noongar. The Krakouer brothers? Noongar. Derek Kickett, Nicky Winmar, Peter Matera? All Noongars.

Of course, the boys playing for Nollamara don’t have to look into history for a connection. Standing on the boundary is former number one draft pick and AFL premiership player Des Headland, who works with the team. Tossing a footy from hand to hand, Headland considers the long-running overrepresentation of his people in the game.

“Why are Noongars so good at footy? I’m not sure. Probably comes down to the history of the people – and this place, yeah?” he says, spinning the ball on a finger. “It’s a good question, eh.”

The white spirits

It all started perhaps 50,000 years ago, after the Nyitting, the long time ago. That is the earliest moment anthropologists can establish a Noongar presence in the region. At that time – and even now – the boundaries of their nation were vast, roping in the entire south western corner of Western Australia, from Geraldton on the west coast to Esperance on the south coast.

It was a place formed by the snake known as Wagyl, who slithered over the land slicing rivers and escarpments into its flesh, whose serpent scales dropped off and became the forests, who coiled his body to make the lakes and bays. Long after his time, after the end of the last ice age, the Noongar stood wrapped in kangaroo skins, watching from the shore as Dutch explorers wrecked their ships against the coast.

When they landed, they found a society who hunted with the kali (boomerang) and the gidjee (spear), who gathered native potatoes and wild onions and bush yams. They found an industrious people who maintained the land with fire but who also – especially during the whorl of a corroboree – would pay heed to the spirits.

The Noongar do not play with fire. The Noongar will not draw in the sand after dark. The Noongar never whistle at night, because they do not want to alert the Wirra Wirra, the bad spirits.

The pale people who landed they called the Djanga, the white spirits. They believed them to be the returned souls of the dead. Their skin was like corpses. Their smell from the voyage was fetid. And they came from the west, the Kuranup, where the sun sets and souls go to sleep. The ghosts brought death with them, too. By communicable disease. By murder.

Noongars were shot for stealing flour, and retaliated with revenge attacks using quartz crystal knives. There were captures, executions without trial, and battles became massacres. June 11, 1829, marks the day sovereignty was assumed over Noongar country and 187 years of dispossession began.

Football was their first thankful freedom, but it did not arrive here for 50 more years, and did not thrive for perhaps another 50 again.

An astonishing anomaly

Paul Roberts, who has studied the history of the Noongars and directed a 1988 cult documentary about their sporting success, Black Magic, lives in Fremantle. He’s chosen a cafe in this once rough port city, now shared with backpackers, at which to talk.

Roberts describes the wild bloodshed of white invasion as well as the formal domination: the land barons who exploited native labour and flogged the defiant. As a white child growing up north of Albany in the 1960s, he saw the old whipping posts.

It pleases him to think of Noongars now on the national stage, making opponents look foolish.

“It is a story of spectacular over-representation. An astonishing anomaly,” he says.

But you talk to a white person in the street here and they go, ‘What’s a Noongar?’

“The fact that we don’t know – that we think they simply identify as Aboriginal or Indigenous – identifies a terrible gap in our thinking.”

He traces a line through Noongar footy history from Jimmy Melbourne, who played in a 1901 West Perth premiership team and was later killed in South Melbourne, to the Hayward brothers of the 1930s, who honed their skills by kicking through the forks of Karri tree branches. Later came dominant stretches from champions Ted “Square” Kilmurray (1950s) and Graham “Polly” Farmer (1960s), who both grew up in the care of Sister Kate, an Anglican nun who raised mixed-descent Aborigines in various cottage homes. Stephen Michael, perhaps the greatest player to resist the VFL, came from Kojonup, in the heart of Noongar country. Barry Cable, the legendary rover, was a contemporary from Narrogin, 125 kilometres away.

Roberts visited countless such places when he filmed the documentary. They were pretty little towns with grim histories, where Noongars were shunted to the margins, denied schooling and arrested if they were seen on the streets after 6pm. “I remember one place, an Aboriginal reserve outside of Doodlakine, 220 kilometres east of Perth, which was home to various Yarrans and Kicketts,” Roberts says. “It was a rubbish tip on one side, a quarry on the other.”

From these experiences, the Noongars developed a certain defiance. AFL legend Kevin Sheedy recently called the Noongars a warrior tribe (“The Zulus of this nation”), and Roberts agrees. He thinks that mindset comes back to one word.

He writes it down in blue pen: winyarn.

“It means scared, or soft, or weak,” Roberts says. “You can’t be winyarn. You just can’t. To the Noongar, if someone has wronged you, you’ve gotta face them. Doesn’t matter if he’s twice the size, if he’s a cop, if there are three of them. You stand up.”

That little bit of chemistry

On a recent Friday morning, the sun bakes Fremantle Oval. Inside the ageing and soon-to-be-replaced Dockers’ training facility sits Roger Hayden, who was appointed development coach in 2011 following a 128-game career with the club. He is one of only two Indigenous coaches in the AFL, both in development roles. It is a sore point for the league, which at the senior level has only ever had two Indigenous coaches. (Both were Noongars: Farmer and Cable.)

Hayden grew up in Brookton and through his parents is connected to Noongar football royalty – on his dad’s side, the Bennells, Kicketts, Boltons, Ugles, McGuires, Jettas, Yarrans, Collards and Davises, and on his mum’s, the Haywards, Eades, Coynes and Flugges. Part of his job involves supporting men with similar lineage.

I’m Noongar, and if they’re Noongar our families are going to know each other.

“I think that’s the beauty of it – we can work through whatever’s going on. We have that little bit of chemistry.”

Of course, it doesn’t always work out. Josh Simpson, a sublimely gifted player drafted to the Dockers in 2012 with pick 17, played two games in two years and was fined twice by the club for failing to meet club requirements. He was then delisted.

“It does sting, although he was a young man looking after two kids with an AFL career – not your typical school leaver,” says Hayden. “But he’s back at East Fremantle now having another crack at it in the WAFL, and that’s fantastic. His contact with footy has been positive.”

Hayden walks into a function area where dozens of young Aboriginal boys are watching a video. The star-struck kids – half of whom are Noongar – are from the Clontarf Foundation, an educational program that encourages Aboriginal boys to learn by integrating their schooling with a football academy, using training and games as the carrot for study and self-improvement.

Clontarf started with 25 boys and two staff at one school, and now has 4210 students and 220 staff working in 68 schools around the country. Since the program was established in 2000, 35 players have also made it onto AFL lists, including more than a dozen Noongars, 2013 All Australian centre-half back Michael Johnson foremost among them.

Johnson is here today. The key defender’s 2016 season has been ruined by long-term knee and hamstring injuries, but in between a massage appointment and other rehab duties, he stops to talk. Johnson was raised in the suburbs of Perth. Walking around the streets he was never without a football. “I would always find goals, whether it’s two bins or two bushes close together,” he says. “You never lose that feel for the game. Watch Stephen Hill running off the wing for us, or Michael Walters kicking goals. It’s the sport we grow up and play and love. Communities get together and mingle. We talk about footy. It makes us stronger.”

The man who runs the Clontarf Foundation is Gerard Neesham, the inaugural coach of the Dockers, and he remembers Johnson well. Good Weekend catches up with Neesham over coffee in Melbourne, where he is meeting potential partners from the private sector.

“Michael was just a really lovely quiet kid, a late bloomer, not overly confident, not recruited out of school, not part of the state Under 18s. His dad passed away prematurely, so he’s had his own heartaches. We helped him a bit with his footy and with school.”

Neesham is adamant Clontarf is not just about sport. The group who visited the Dockers, for instance, were year 12 students on a leadership trip to Perth as a reward for outstanding behaviour in class.

“The ultimate outcome is an employable boy,” he says. “If he happens to be employed by the AFL or Rio Tinto or Woodside, we don’t particularly care, as long as he’s doing something positive with his life.”

Plenty have been saved in this way. Neesham points out that Clontarf alumni and current AFL players Chris Yarran and Lewis Jetta were both “somewhat disengaged” with their education.

“If you’re not engaged in school then you’re invariably not functional, and to be an AFL player – with all the meetings and game plans and lifestyle requirements – you have to be highly functional,” Neesham says. “We didn’t make them any better at playing footy, but we made them a hell of a lot more functional.”

He puts Noongar success down to simple geography. Their territory is proximate to the coast and rich in rainfall, meaning their land was close to every developing farming or industrial town – and the centre of every small town is its footy club.

“Half your footy team was blackfellas, half was whitefellas. That’s the way it was.”

“We didn’t know what we were doing was reconciliation, because we didn’t know there was anything to be reconciled.” The area’s geo-historical connection to footy, he adds, did not occur throughout the rest of the country. It is not even true for the rest of Western Australia.

“Take the Kimberley,” Neesham says. “Basketball was the predominant sport in the Kimberley until 20 years ago. Baseball, because of the Americans that docked there, was the sport in Port Hedland.” No star footballers emerged from the Pilbara until the past two decades, because the game wasn’t historically grounded there.

Neesham has explained a generational talent. How it bloomed into dominance is another story. If you want to know how the Noongars came to the AFL, Neesham says, look at how they first stormed into the WAFL. “You want to talk about the person who made the biggest impact?” he asks. “Talk to Mal Brown.”

Larger than life is no cliché with Mal Brown. He is the forever disgruntled “Richmond power-broker”. The father of Hawthorn hit man Campbell Brown. He is “Fatty” – a nickname that stuck by the burly footballer his entire career.

And he is a “racist” to those who condemned him for his 2010 use of “cannibals” and “little black buggers” as terms of endearment for the Indigenous players he coached.

He, though, sees himself as just a country boy from Dowerin – the town where Noongar superstar Buddy Franklin also grew up. Brown kicked around with Noongar boys as a kid and, as a boundary umpire, watched them grow up. Soon enough he was playing and coaching, most notably at South Fremantle, guiding an unprecedented number of Indigenous players including Stephen Michael, Michael Cockie, Nicky Winmar, Ollie Loo, Willie Roe, Brett and Dean Farmer – but also Maurice Rioli from the Tiwi Islands and Basil Campbell from Darwin.

In the late 1970s, when most clubs had only one or two Indigenous players, Brown began playing as many as eight in a side. Instead of winning games on the back of dour defenders, as was the norm, his Noongar fleet would attack. “You had to forgo team meetings and rigid plans and let these guys play with flair, on God-given instinct,” he says.

“They gave your spectators hope, and gave their people hope.”

They were tough, too. Brown recruited them not for their unfathomable manoeuvres but their composure in mature country leagues. “They had played against men. They knew how to cop a whack,” he says. “If you want to bring your club up from the bottom, you get a bloke who’s physically stronger and quicker, who comes to town and gets a job, and his mates become the people at the club.”

There was little division. If a Noongar player was attacked on the field, his white teammates would fly the flag. It was part of the club’s two-word philosophy: Him’s me.

“If you hit him, you hit me,” Brown elaborates. “They would have copped a lot of sledging on the field because of their race, but there was no preciousness. They didn’t need protection. To look at the list of Noongars I coached, I can’t see one who was a bit scared.”

The Krakouer factor

Back in Perth, zipping past the many suburban ovals dominated by the Noongars, Curtin University academic Sean Gorman explains how the Noongars made the next leap, from the local league to the big dance.

“Is football a way out? Yes. But footy is also something deeply important, and it occupies a psychic space with Noongar people. Does it draw on ancient survival skills? Possibly. Does it allow us to see the spectacle of traditional dance as athletic contest? Yeah, maybe. Does it enable them to express themselves? Yep,” says Gorman, an expert on Indigenous issues and footy. “It’s all of these things that have aggregated to produce this potent magic, and we – the football public – are the beneficiaries.”

The Noongars entered the greater Australian consciousness, he says, in 1982, when the footy highlights show The Winners began broadcasting two brothers tearing the VFL up.

“The Krakouers are recruited to North Melbourne and they hit the league,” says Gorman, punching his hand. “They explode onto the scene. They are big news right from the start. There were individuals before that, but the first time a cohort of black bodies is recruited to one team is Jimmy and Phil. People go through the turnstiles to watch them. Jimmy especially, because he was incendiary. He could seriously fight. He was dynamite with his hands.”

Gorman wrote a book about the Krakouers, Brotherboys, which charts their rise from Mount Barker, near Albany, through their VFL careers – Phil as the line-breaking deadly left foot, and Jim the hard-nut rover – to Jim’s incarceration for drug trafficking after retiring from the game.

Talking to Jim Krakouer on the phone, his voice is little more than a warm mumble, yet his childhood memories are vivid and clear as he recounts his beginnings on an Aboriginal reserve near Bunbury, in a tin shed with no water, no power.

Krakouer says his parents put in “a mighty effort” – Dad as a shearer and Mum raising 13 children – but the only thing that gave him joy was football. “Skins and shirts. A good old game of rough and tumble. Where we come from, you had to really try hard, fight hard, struggle hard,” Krakouer says. “Off the field, I used to go into my shell. But out there, you felt confident. Footy was a way of getting on level ground with the rest of the world.”

That was no mean feat. The Stolen Generations have their roots in Noongar territory. Ground zero for widespread Aboriginal child removal was the appointment of Auber Octavius Neville as Chief Protector of the Aborigines in Western Australia in 1915. Entire towns were stripped of their Indigenous population, who were sent to settlements and missions. Perth was declared a prohibited area for Aboriginal people between 1927 and 1954, and Noongars required a permit to enter the city.

Gorman often asks his students to name a few Indigenous people. They invariably list footballers. Then he asks for names not associated with sport. Someone might say actor Ernie Dingo, painter Albert Namatjira or singer Jessica Mauboy. The politically aware know Pat Dodson, but that’s it. And that’s why football is so important.

“They still feel like they’re in a state of siege here,” Gorman says. “The form of the war has changed, but you still have a dispossessed people who live in a society not of their making. When you hear the story of a footy player like Jimmy Krakouer, you’re weaving his turbulent career into a socio-political tapestry, and that’s powerful. It’s a common language. Think about it. What would you know about Aboriginal people without footy?”

Kick the thing

Invoking genetics to explain athletic performance is a dangerous game. Yet we freely acknowledge the fast-twitch muscle fibres of star African American athletes, and marvel at the tapered calves of distance-running Kenyans. Larry Kickett, the first indigenous member of the West Australian Football Commission, is happy enough to follow suit. “Aboriginal people anywhere, their hand-to-eye co-ordination is very good,” he says. “They have got this sixth sense, and you see it on the field. You see a guy and think ‘He’s gonna get clobbered, or cleaned up,’ and then all of a sudden he’s not there. He’s gone. They know their surrounds.”

Football ability is in Larry Kickett’s blood. Derek Kickett is his first cousin. Dale Kickett, Jeffrey Garlett and Buddy Franklin are his nephews. He grew up in Tammin, where his family worked on wheat and wool farms. They bent their back, he says, and did the job properly. Kickett believes such work – combined with millennia spent hunting and gathering – created a unique athletic alchemy.

“The Noongars’ success is built on 50,000 years of life and culture and work.”

“It’s not hard for us to pick up a football and kick the thing.”

Retention is the challenge. That’s what Paul Mugambwa, a community engagement officer with the Western Australian Football Commission, says. He works with and monitors pathway programs designed to nurture Indigenous talent. The Nicky Winmar Carnival, for instance, draws 400 of the best Indigenous teenage boys from the region, and the top 22 end up in the AFL-run KickStart Championship team, playing off against other states.

Western Australia, with its mostly Noongar sides, has won the past five years. It should be a point of pride, yet Mugambwa notices the drop-out rate rising. Juniors join regional teams, then the state program, then leave the game altogether.

He mentions one: a star on the field, but school is a problem, as are his friends. His parents are absent. He sleeps in a different bed each week. All the while, the demands of the sport are growing. “He’s training three times a week, plus a game, plus he needs to look at his nutrition, plus he needs an extra weights session, skin folds measurements, understanding a game plan. It’s hard to know whether he’ll make it or not.”

Support systems are strained at all levels. More liaison officers are needed. For every Des Headland, he says, there are a dozen Noongars who were just as good but slipped off the football factory conveyor belt.

“The Noongars have produced an amazing amount of talent, but we haven’t even scratched the surface yet,” Mugambwa says. “The worry is we could become a victim of our own success. If 30 Aboriginal boys suddenly get drafted, will the system be ready? Will the clubs be able to cope? Is a kid from Wangkatjungka going to survive at Greater Western Sydney?”

A chance

The rain falls thick and cold on this Saturday in Perth, as Noongar elder Richard Walley stands outside Domain Stadium just prior to the Dockers-Richmond match. Walley is the No. 1 ticket holder for Fremantle this year, and will deliver the Welcome to Country before the bounce. He is an expansive and generous talker, who sees football as a way forward for his people. Walley loves the idea of sport as a form of organised but casualty-free war, and footy especially as an epicentre of racial harmony.

“That’s an Australian thing as much as a Noongar thing. You see all the players after the game, locking arms to say hello and have a genuine conversation,” he says.

“The goals, the ball and the boundary line don’t recognise race or colour or size. They recognise nothing.”

“There are only two things in the art of football – execution and opportunity. You have to perform, and be given a chance or an opening.”

A chance is what Walley’s friend, Nick Abraham, is working on – at least when he isn’t shivering as this storm rolls in off the ocean, waiting with Walley for the game to start. Abraham is the head of the South West Aboriginal Land and Sea Council, the native title body for the Noongars, of whom there are about 30,000. He is well versed in the disadvantages facing the traditional landowners. The suicide rate is three times the rate for Indigenous people in Western Australia as for non-Indigenous people. Life expectancy is 11 years less, and the rate of imprisonment is 3663 per 100,000 compared to 164 per 100,000.

But there are positive signs. In 2014, the Noongars negotiated a $1.3 billion native title settlement – the largest in history – covering 320,000 hectares of land, including Perth. It will never be enough, but it does offer an opening.

“It’s an opportunity to get our mob connected, and get our identity back,” Abraham says. “It’ll be spent on grassroots. People living in poverty. It’ll spur enterprise, rebuild the culture, and give our mob a fair go. In the meantime, we have football.”

A scary mix

Back at Nollamara, Des Headland is doing what he can. Two nights a week, he and other members of the club drive around the neighbourhood, picking up players and ferrying them to training. Some are from happy homes, others from overcrowded digs with little food, and still others from drug and alcohol rehab centres. The club rooms – with the big open fire place at its heart – is a gathering space for their community.

“People from the East, they picture red dust, bare feet, dark skin, out on a reserve,” says Headland. “But it’s just not the reality. Most Aboriginals are like us, urbanised blackfellas. And they’ve got challenges with drugs and alcohol, depression, suicide, poverty.”

He’s noticed there is something perhaps less carefree about Noongars than other tribes, and it’s reflected in their footy. He calls the skinny boys from northern Australia “tap-tap” footballers, for instance, because of the way they flick the ball along the ground and playfully scoot through packs.

The Noongars, Headland says, developed different playing styles in different climes, in the mud near the jarrah forests, on the semi-arid plains where grain silos loom, and on the concrete expanses and patchy grass of the city. He guesses they bring the toughness of the farm leagues near the coast, where the “Great Southern boys” pour milk on mallee roots for breakfast. The outside speed of the “Wheatbelt blokes” in the wide-open spaces of their slowly dying towns. And certainly the desire of “city blackfellas”, who play on the sandy soil of suburban ovals like this one, where the spotlight is bright.

Yeah, he says, it’s a combination of people and place, geography and history, resistance and resilience. “In Noongar footy, it all comes together,” says Headland, drilling a ball into the night. “It’s a scary mix.”

This story first appeared in Good Weekend on July 2, 2016. (Konrad remains amazed by Noongar society.)